Alzheimer’s disease is more than a news story for me. It’s very personal. This disease is making headlines this week because of a story about famed restaurateur Barbara Smith aka B. Smith who was diagnosed in 2014. Her husband, Dan Gasby, is coping in a nontraditional way and many people have strong opinions about his choice. It’s become the latest “what would you do?” reminding me of what I could not do.

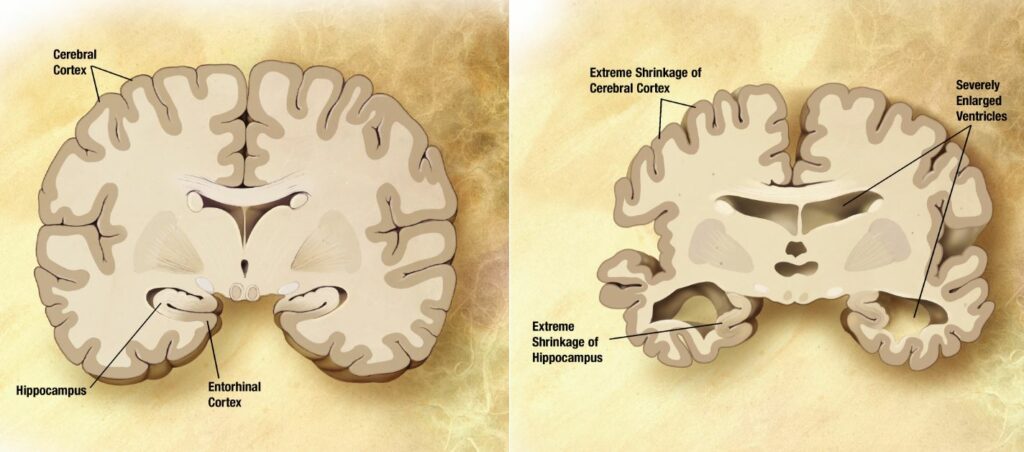

My paternal grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 1980. Alzheimer’s is a brain disease that progresses slowly causing problems with memory, language and disorientation. My grandmother successfully hid her mental lapses from us for a while. Then, one day, she almost burned her house down because she forgot about the food frying on her gas burner. Her doctor insisted the family be informed about her condition. HIPAA privacy laws be damned.

As fate would so decree, the closest living relative was me. I am the only child of an only child. My father and grandfather died before I was promoted to middle school. At the time of my grandmother’s diagnosis, I was a teenager living with the parents I still call Mom and Dad.

I remember traveling to grandmother’s house with my mother. We convened in the kitchen around the square table with the yellow Formica top and ribbed aluminum trim. The room smelled faintly of Pine Sol. It always had the aroma of food or Pine Sol. The discussion was brief. There weren’t many options. Of the ones presented, my grandmother chose the nursing home. And we could not change her mind.

Yet, as I watched her wipe the same spot on her countertop, the faded, floral dish towel winding around, over and over, I knew she preferred to remain in her home. Inimitable and independent, a college educated African-American woman born in 1899. She only bowed her head to pray. For so many reasons, it was a sad day.

At that time, there were mostly good moments filling mostly good days. So she packed her things herself and stored them away. The first few months in the nursing home, she seemed depressed, but she was lucid. Our visits became increasingly difficult as she struggled to recognize me. Sometimes she seemed perfectly fine except that her conversation was from a period fifteen years in the past. As the months went by, she seemed to spend more and more time reminiscing.

I thought she did that because it was a happier time, when her husband and son were alive. Then, it occurred to me that she was still packing–packing her memories–starting with the most recent. When she was done, she stored them, too, and locked them behind eyes that didn’t focus and a mouth that didn’t speak.

Years went by. I would visit her warm body as often as I could. It was clear to me that her mind was like the living room in her old house. I was not allowed entry to either. Eventually, she stopped swallowing. The remaining hours of her life seemed as short as the space between the last letter of this sentence and the period.

Perhaps you wonder why I share this story, so personal and still so painful. Frankly, I’m storing my memories, too, and I never want them locked away where no one, including me, can retrieve them.

@drmoeanderson. 2019 All rights reserved. Monica F. Anderson

Author of “Success Is A Side Effect”